The first night of my homestay during the Zapatista Little School, my guardian and her husband asked if their students had any questions. My classmate and I both had experience working with the Zapatistas, so we politely limited ourselves to the safe questions that are generally acceptable when visiting rebel territory: questions about livestock, crops, local swimming holes, and anything else that doesn’t touch on sensitive information about the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN).

My guardian’s husband patiently answered our mundane questions. Then he said, “Look, we entered into clandestinity in 1983, when the organization was just being formed. We walked hours at night to organize other towns, always at night so that the plantation owners wouldn’t get suspicious, and we went into the brush to train. My wife risked her life walking at night to bring bags of tostadas to the camps so that the insurgents would have food to eat during training. Now, do you have any other questions?”

My classmate and I looked at each other, our eyes seeming to say the same thing: “Oh, so that’s how it’s going to be at the Zapatista Little School.” Then our questions began in earnest, and our guardians and their neighbors enthusiastically answered every single one.

Setting the Record Straight

The Zapatistas made the decision to open up their homes to their long-time supporters and teach them about their past, present, errors, victories, and advances for several reasons. During the Little School, Zapatistas repeatedly said that they hoped their supporters could learn from their experiences.

“Self-governance… is possible. If we achieved it with just a few compañeros andcompañeras, why not with thousands or millions?” asked a Zapatista woman from Oventik. “We hope you’ll tell us if our practice, our experience with self-governance is in some way useful for you.”

“Many people think that what we’re doing, our form of governance, is a utopia, a dream,” said another Zapatista in Oventik. “For us Zapatistas, it is a reality because we’ve been doing it… through daily practice over the past 19 years. And that is why we think that if we join together with millions of Mexicans, we can form our own governments.”

Years ago, a Zapatista told me that they often learn more from their mistakes than from their victories. In that spirit, the Little School curriculum includes brutally honest discussions about errors the Zapatistas have committed over the years. For example, the textbooks include a frank discussion about the demise of the Mut Vitz coffee cooperative in 2007. Even though the cooperative’s sudden, unexplained closure was felt throughout the United States and Europe when roasters suddenly found themselves without a source of Zapatista coffee, the Zapatistas had not explained the reasons for Mut Vitz’s downfall until now.

In the Little School textbooks, Roque, a former member of the cooperative and current member of the San Juan de la Libertad Autonomous Municipal Council in Oventik, reveals that mismanagement and corruption ultimately lead to Mut Vitz’s demise. The cooperative had hired an outside accountant who, for reasons unknown to the cooperative members, did not accurately declare Mut Vitz’s assets to Mexico’s tax agency, which allowed the government to freeze their bank account. As Mut Vitz underwent an internal audit to determine what money the cooperative had left outside of the frozen account to pay producers who had supplied coffee on credit pending its sale, the Oventik Good Government Council discovered that members of the Mut Vitz board of directors were stealing money from the cooperative. The Council issued an order to arrest the guilty parties and seized some of their assets to replace the money they had stolen.

The Zapatistas also hoped to use the Little School to set the record straight about the state of their movement. They read the news, and they told students that they know the corporate media reports that Zapatismo is a dying movement, that the Zapatistas have turned their guns over to the government, that Subcomandante Marcos died of lung cancer or was fired, that the Comandancia (the Zapatista military leadership) meets secretly with the “bad government” and accepts millions of pesos from it, and that the Zapatistas are closet communists, amongst other baseless claims.

Furthermore, the Zapatistas admit that there have been traitors, compañeroswho left the organization and collaborated with the government. As one European activist said at the end of the Little School, “I think they realized that it had gotten to the point where Mexico’s security agencies knew more about how the Zapatistas’ government works than their own civil society supporters did, so they decided to let us in on what they’ve been up to.”

The Zapatistas’ civilian government is, after all, not clandestine, and non-Zapatista indigenous people routinely use its clinics, justice system, public transportation permits, and other services that they can’t seem to obtain through the Mexican government. Moreover, any non-Zapatista—be it the bad government or another indigenous organization—that wants to develop an infrastructure project that passes through Zapatista territory (roads or electricity, for example) must negotiate with the Zapatistas’ “good government” and therefore understands how it is structured. With the Little School, the Zapatistas have officially and for the record explained exactly how their government works.

Perhaps one of the Little School’s most important benefits for the Zapatistas occurred during its preparation. The Little School’s four textbooks, Autonomous Government part I and II, Women’s Participation in the Autonomous Government, and Autonomous Resistance, as well as the two DVDs that accompany the books, were all created by Zapatistas themselves. The textbooks are the result of Zapatistas from all five caracoles (Zapatista government centers) traveling to regions other than their own to collect testimonies and interview fellow Zapatistas about how they self-govern.

The Zapatistas’ bottom-up approach to government means that while all of the caracoles operate under the same basic principles and towards the same goals, their day-to-day operations sometimes differ drastically. For example, every caracol has a Good Government Board, the maximum governing body in the region. However, each caracol’s Board is structured differently. Many of the Zapatistas’ questions to their compañeros from other caracoles in the interview portion of the textbooks revolved around their experiences and what has worked and what has not.

For example, a Board member from Oventik asked former Board members from Morelia, “Are the twelve members of the [Morelia] Board able to do all of their work? Because in Caracol II [Oventik] there’s 28 of us, and sometimes we feel overwhelmed.” The Morelia Zapatistas’ response was that they, too, are overwhelmed, and they feel the need to restructure the Board, but they have been unable to come up with a better proposal thus far.

Governing from Below

When the Zapatistas rose up in arms in Chiapas on January 1, 1994, they knew they wanted freedom and autonomy. “But we didn’t have a guide or a plan to tell us how to do it,” a Zapatista education promoter explained to me. “For us, it’s practice first, then theory.”

While part of the EZLN drove rich landowners off of their plantations in the Chiapan countryside in the pre-dawn hours of New Year’s day, other contingents took seven major cities around the state. “All that we’ve accomplished was thanks to our weapons that opened up the path that we are walking down today,” explains a Zapatista from Oventik on a Little School DVD. “[Since then] everything that we have achieved, we have achieved without firing a single shot.”

Immediately following the uprising, the Zapatistas implemented autonomous government at the town level. Each town named its local authorities and formed an assembly. “But since we were at war, we kept losing local authorities,” explains Lorena, a health promoter from San Pedro de Michoacán in La Realidad. “There was disorder in the communities.” As a stopgap measure, the EZLN’s military leadership had to step up and fulfill roles that civilian authorities were unable to carry out during the chaos of the war.

The military leadership held consultations with civilian authorities, and together they decided to create autonomous municipalities in order to bring order and civilian governance to the rebel territory. In December 1994, the Zapatistas inaugurated 38 autonomous municipalities comprised of an undisclosed number of towns. Each autonomous municipality had its own municipal council named by the towns, allowing for increased coordination between towns and more formal organization of civilian affairs.

As solidarity activists began to arrive in Zapatista territory to donate money and labor, the EZLN’s command realized that some municipalities were receiving more support than other, more isolated ones. “At [the command’s] urging, the municipal councils met and began to hold assemblies to start to see how each municipality was doing, what support each was receiving, what projects were being carried out,” explains Doroteo, a former member of La Realidad’s Good Government Board.

In 1997, the Zapatistas formalized the assemblies of municipal councils by creating the Association of Autonomous Municipalities, comprised of representatives from each autonomous municipality. “With the association of municipalities, tasks and work in health, education, and commerce were overseen,” recalls Doroteo. “During that time a dry goods warehouse was created… with the idea of [economically] supporting the full-time workers in the [Zapatista] hospital in San José del Río.”

During the creation of the Association of Autonomous Municipalities, the Zapatistas formally redistributed the land they had taken over in the 1994 uprising. Landless Zapatistas left the communities in which they were born to settle on recuperated land they could finally call their own, fulfilling revolutionary hero Emiliano Zapata’s creed, “The land belongs to those who work it.”

In 2003, the Zapatistas inaugurated the third level of their autonomous government, the five Good Government Boards, located in La Realidad, Oventik, La Garrucha, Morelia, and Roberto Barrios. However, the organization of higher levels of government does not mean that the Zapatistas are moving further away from direct democracy through local assemblies. On the contrary, all proposals must be approved by town assemblies.

Proposals can originate in town assemblies and work their way up the different levels of autonomous government if they affect more than just the town in which they originated. The proposals pass through the municipal councils, which then brings approved proposals to the Good Government Council, which then runs them by the command, which then sends the proposals back down through the five Good Government Boards, which send them to the municipal councils, which in turn send the proposals to the people at the town level for consultation and implementation.

The command can also create its own proposals and send them down through the three levels of civilian government to the town assemblies for consultation and approval. Therefore, even though the Good Government Boards are the highest level of the autonomous government, they have no authority to create laws. The Boards are limited to two main roles: to coordinate and promote work in their regions and to enforce and carry out Zapatista laws and mandates that have already been approved by the people.

Because the Zapatistas constructed their government from the bottom up, with people organizing themselves into community assemblies, which in turn organized municipal councils, which in turn organized the five Good Government Boards, everyCaracol is different. All work to implement the Zapatistas’ demands: land, housing, health, education, work, food, justice, democracy, culture, independence, freedom, and peace. However, the Zapatistas’ progress in implementing those demands varies from Caracol to Caracol. Some Caracols, such as La Garrucha, have collective economic projects such as stores or cattle to fund political activities at each of the three levels of government; other Caracols like Oventik only have collective economic projects in some towns.

Likewise, methods and success in implementing the Zapatistas’ Revolutionary Women’s Law varies. Morelia, for example, struggles to find ways to promote women’s participation in the higher levels of autonomous government. However, Morelia is unique amongst the Caracols because its Honor and Justice Commission (the judicial system) has a special plan for dealing with rape that aims to reduce re-victimization and encourage women to report crimes.

Constant Progress

Many have referred to recent Zapatista mobilizations such as their December 21, 2012, silent march and the creation of the Little School as a Zapatista “resurgence.” The Little School left one thing very clear: this is not a resurgence, because the Zapatistas never went away. During the school, students learned about the seemingly endless new cooperatives, the Zapatistas’ experiments in collective governance that are always being fine-tuned, and how donations from supporters were invested in livestock and warehouses so that they would pay dividends that would provide a steady long-term budget for hospitals and clinics.

The Little School’s lesson is clear: if the Zapatistas aren’t talking to the press, don’t commit the error of thinking that they are losing steam or have faded away. They are simply working extremely hard to advance their autonomy, and are too busy to get bogged down in countering the naysayers.

After all, their success is measured in their achievements and not their rhetoric. As one Zapatista man said at the end of a Little School class in Oventik, “We are demonstrating to the bad government that we don’t want it and we don’t need it, and it’s not necessary, for us to provide for ourselves.”

Kristin Bricker is a reporter in Mexico. She is a contributor to the CIP Americas Program www.cipamericas.org.

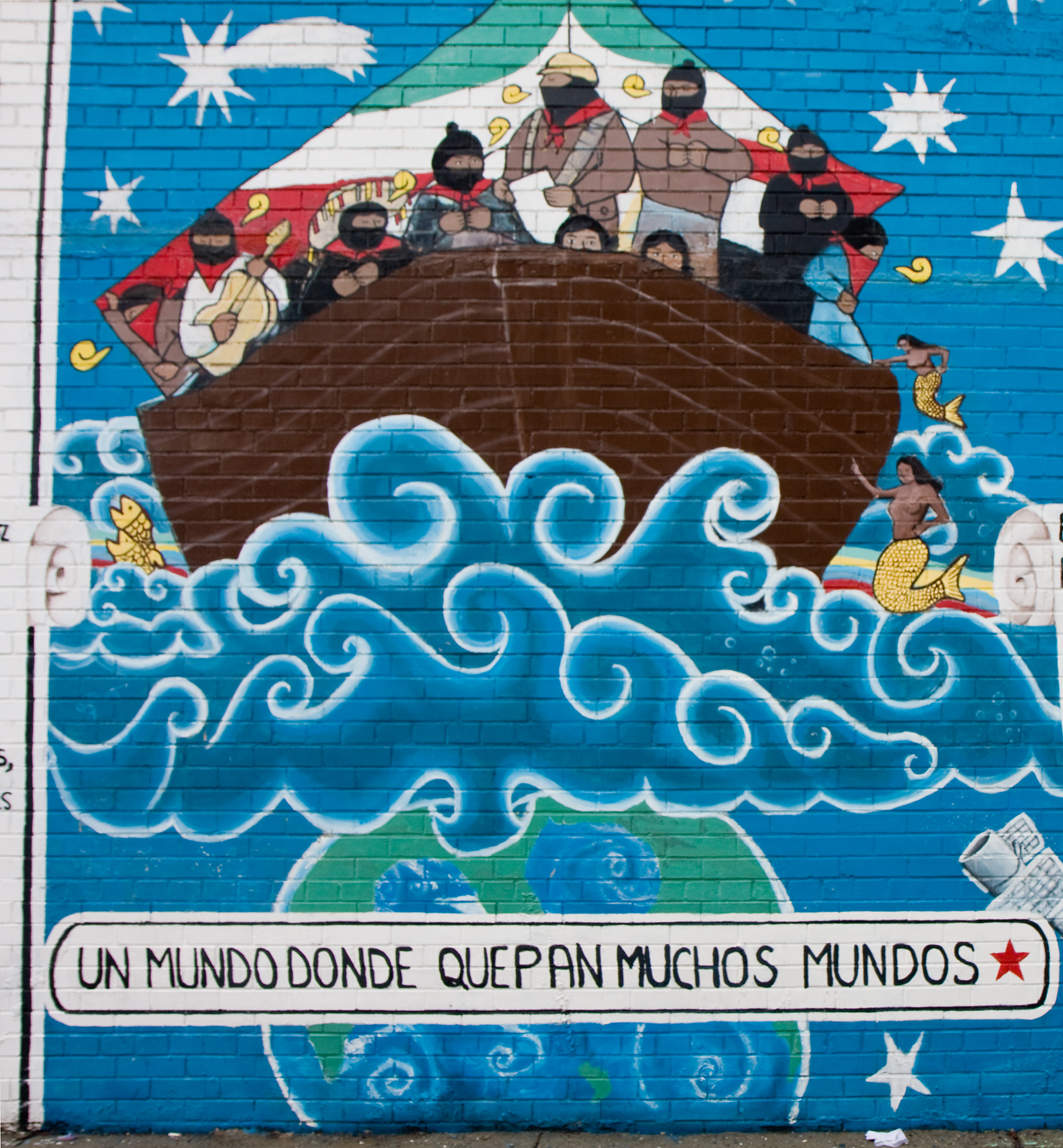

Photos: Santiago Navarro F