August 26, 2010

by EFE

Rio de Janeiro - The Mexican government's decision to militarize the fight against drugs increased drug trafficking violence, agreed experts who participated in the Second Latin American Drug Policy Conference in Rio de Janeiro.

The violence in Mexico, made worse by the massacre of 72 immigrants at the hands of alleged drug traffickers, was cited by various conference participants as an example of the failure of the current drug policy. Alternative policies were supported in the conference.

"The fact that drug policy is conceived of as a war on drugs is what has provoked the escalating violence in Mexico," said Juan Machín, director of the Cáritas Training Center, an organization that treats drug addicts in Mexico City.

"We believe that it is necessary to adopt non-repressive security policies. Our countries understand very well the deadly consequences of the militarization of conflicts, such as that which Mexico is experiencing today," said Argentinian Graciela Touzé, president of the Intercambios Civil Association.

According to Touzé, despite the fact that in some countries in the region there is a discourse that recognizes the failure of the war on drugs, that discourse still hasn't translated into concrete policies that treat drug users and end the violence.

Machín told EFE that Mexican President Felipe Calderón committed one of his worst errors when he sent the military to the streets because he conceived of it as a "war" instead of a struggle against drugs.

"The perverse effect that militarization has had is that it has generated a bigger wave of violence, and the President's decision to not back down has provoked an almost exponential increase in violence. We began with some 2,000 murders per year, and in 2009 we had 8,000. We now have a total of almost 30,000 deaths [since Calderón first deployed the military in late 2006]," said Machín.

The expert believes that the situation could get even worse if that policy doesn't change. "And the president [Calderón] is in up to his neck and won't change course. It is having a very high political cost, but he knows that if he backs down it will have a worse political cost, because it would mean admitting that his policy is a disaster," he added.

According to Machín, rather than a war, Mexico needs a comprehensive policy to combat drug trafficking that includes economic and social measures to reduce poverty and unemployment, a security policy that is based in intelligence work and prevention, harm reduction, and even legalization.

"Ending the drug problem with a stick, be it through the police or militarily, the most that will be achieved is a small degree of reduction. As long as social problems go unresolved, there will not be a solution," agreed Colombian economist Francisco Thoumi, the author of multiple books on drug trafficking.

"This is why the infamous war on drugs has gone on for 40 years, and every time there's some sort of gain, the industry adapts and evolves," said Thoumi, an investigator with the Center for the Study of Drugs and Crime at the University of Rosario.

According to Thoumi, the problem is that in countries such as Colombia and Mexico, it became acceptable that some groups violated the law, and society ended up tolerating corruption and criminality.

"Without a doubt, palliative policies can be improved, and one could talk about the possible effectiveness of militarization or the effectiveness of marijuana legalization, but as long as social vulnerabilities are not identified, there won't be a solution," he said.

Luiz Paulo Guanabara, director of the Brazilian Center for Drug Policy, argued that any policy that insists on militarization and the criminalization of drugs is doomed to fail.

"Those policies only produce violence, like in Mexico, where it is already intolerable," he said.

Translated by Kristin Bricker

Tuesday, August 31, 2010

Tuesday, August 24, 2010

Triqui Women on the Frontline in San Juan Copala Conflict

A New Ambush Aimed at the Women-Led Caravan Leaves Three Dead; Caravan Postponed

by Kristin Bricker

The paramilitaries who invaded San Juan Copala, Oaxaca, this past July 30 have since abandoned the autonomous municipality's town hall. They didn't go far, however, and near-daily shootings from the paramilitary sharpshooters stationed around the town keep San Juan Copala under a state of siege.

San Juan Copala declared itself autonomous following the 2006 uprising that nearly drove Oaxaca's governor out of office. The Union for the Social Well-being of the Triqui Region (UBISORT), a paramilitary organization founded by the Institutional Revolution Party (PRI, which has ruled Oaxaca for eighty years), has kept San Juan Copala under siege since January. UBISORT has blocked the road into town with boulders and logs, forcing Copala residents to use trails through the woods to bring in desperately needed supplies on their backs. UBISORT snipers are positioned in the hills surrounding the town, making it extremely dangerous for residents to leave their homes at all.

"No one can go outside in Copala," says Mariana Flores, a representative of the autonomous municipality. "If they [paramilitaries] see you on the street, they will shoot at you."

Residents believe that the paramilitaries are more likely to kill men than women. According to Flores, "If men try to go outside, they don't take more than two steps before [the paramilitaries] try to hurt or kill them."

As a result, Triqui women are playing increasingly vital roles in San Juan Copala. "In San Juan Copala, it is mainly women who risk their lives to go out and look for food," says Flores. When paramilitaries raided San Juan Copala with the help of Oaxacan state police this past July 30, it was women who attempted to repel the invasion. "Women have decided to demand their rights, and now it is women who are struggling for the community," reports Flores.

Women's increasingly protagonistic role in the conflict means that they now bear the brunt of the paramilitaries' violence. Over the past four months:

On August 11, Triqui women took their fight to the state capital and are now occupying Oaxaca City's main plaza. They expect their protest encampment to grow as more and more Triquis who have been displaced by the violence converge on the state capital. The women say they will stay in Oaxaca's main plaza until the government brings the people responsible for dozens of murders in the Triqui region to justice. "We haven't received any response from the government," reports Flores. She says that governor-elect Gabino Cué has not responded to their demands either.

The women had planned to travel to Mexico City on Monday, August 23, to meet with social organizations in an attempt to gain more support. However, the caravan was postponed following an ambush on August 21 that killed three men associated with the autonomous municipality and injured another two. Amongst the dead is Antonio Ramírez López, the leader of Santa Cruz Tilapa, a community that belongs to the autonomous municipality. Ramírez López was one of the founders of the autonomous municipality. The five men were helping organize the women's caravan, and the Bartolomé Carrasco Briseño Human Rights Center says that the men were ambushed as they travelled in a pick-up truck to pick up Triqui women who were supposed to participate in the women's caravan. Forensic investigators report that AK-47s and AR-15s were used in the ambush. Both weapons are classified as exclusively for military use, and it is illegal for civilians to own them.

The autonomous municipality claims that paramilitaries from both UBISORT and the Movement for Triqui Unification and Struggle (MULT) participated in the ambush, although at this point survivors have not identified their attackers.

Organizers in the women's protest encampment in Oaxaca City say that they will remain in the capital's main plaza until their demands are met. They are currently in the process of reenforcing the protest encampment with more supporters. The reenforcement is a security precaution because Rufino Juarez, the leader of UBISORT, was seen on Saturday and Sunday near the women's protest encampment. Juarez has personally participated in assaults against Triqui women, including the May 15 kidnapping of twelve women and children.

by Kristin Bricker

|

| Photo: José Carlo González, La Jornada |

San Juan Copala declared itself autonomous following the 2006 uprising that nearly drove Oaxaca's governor out of office. The Union for the Social Well-being of the Triqui Region (UBISORT), a paramilitary organization founded by the Institutional Revolution Party (PRI, which has ruled Oaxaca for eighty years), has kept San Juan Copala under siege since January. UBISORT has blocked the road into town with boulders and logs, forcing Copala residents to use trails through the woods to bring in desperately needed supplies on their backs. UBISORT snipers are positioned in the hills surrounding the town, making it extremely dangerous for residents to leave their homes at all.

"No one can go outside in Copala," says Mariana Flores, a representative of the autonomous municipality. "If they [paramilitaries] see you on the street, they will shoot at you."

Residents believe that the paramilitaries are more likely to kill men than women. According to Flores, "If men try to go outside, they don't take more than two steps before [the paramilitaries] try to hurt or kill them."

As a result, Triqui women are playing increasingly vital roles in San Juan Copala. "In San Juan Copala, it is mainly women who risk their lives to go out and look for food," says Flores. When paramilitaries raided San Juan Copala with the help of Oaxacan state police this past July 30, it was women who attempted to repel the invasion. "Women have decided to demand their rights, and now it is women who are struggling for the community," reports Flores.

Women's increasingly protagonistic role in the conflict means that they now bear the brunt of the paramilitaries' violence. Over the past four months:

- UBISORT murdered Bety Cariño, a non-Triqui Oaxacan community organizer, along with Finnish observer Jyri Jaakkola, during an aid caravan to San Juan Copala on April 27. It is believed that Cariño was targeted.

- On May 15, UBISORT leaders beat and attempted to kidnap two Copala women. Later that day, UBISORT members kidnapped 12 women and children who had snuck out of San Juan Copala to purchase food.

- On May 20, unidentified assassins murdered Cleriberta Castro Aguilar and her husband Timoteo Alejandro Ramírez, one of the founders of the autonomous municipality.

- On June 24, sharpshooters shot and wounded 8-year-old Miriam Martínez in San Juan Copala.

- On June 26, sharpshooters shot and wounded Marcelina de Jesús López and Celestina Cruz Ramírez as they left a meeting in San Juan Copala.

- On July 26, Maria Rosa Francisco disappeared near her home in San Juan Copala when sharpshooters opened fire. She had left her house to look for firewood and is feared dead.

- On July 30, when women attempted to repel the paramilitary/police raid on San Juan Copala, two girls aged 17 and 14 were shot. The 14-year-old was paralyzed when a bullet fired by the UBISORT lodged in her spine.

On August 11, Triqui women took their fight to the state capital and are now occupying Oaxaca City's main plaza. They expect their protest encampment to grow as more and more Triquis who have been displaced by the violence converge on the state capital. The women say they will stay in Oaxaca's main plaza until the government brings the people responsible for dozens of murders in the Triqui region to justice. "We haven't received any response from the government," reports Flores. She says that governor-elect Gabino Cué has not responded to their demands either.

The women had planned to travel to Mexico City on Monday, August 23, to meet with social organizations in an attempt to gain more support. However, the caravan was postponed following an ambush on August 21 that killed three men associated with the autonomous municipality and injured another two. Amongst the dead is Antonio Ramírez López, the leader of Santa Cruz Tilapa, a community that belongs to the autonomous municipality. Ramírez López was one of the founders of the autonomous municipality. The five men were helping organize the women's caravan, and the Bartolomé Carrasco Briseño Human Rights Center says that the men were ambushed as they travelled in a pick-up truck to pick up Triqui women who were supposed to participate in the women's caravan. Forensic investigators report that AK-47s and AR-15s were used in the ambush. Both weapons are classified as exclusively for military use, and it is illegal for civilians to own them.

The autonomous municipality claims that paramilitaries from both UBISORT and the Movement for Triqui Unification and Struggle (MULT) participated in the ambush, although at this point survivors have not identified their attackers.

Organizers in the women's protest encampment in Oaxaca City say that they will remain in the capital's main plaza until their demands are met. They are currently in the process of reenforcing the protest encampment with more supporters. The reenforcement is a security precaution because Rufino Juarez, the leader of UBISORT, was seen on Saturday and Sunday near the women's protest encampment. Juarez has personally participated in assaults against Triqui women, including the May 15 kidnapping of twelve women and children.

Labels:

APPO,

autonomy,

land and territory,

Oaxaca,

paramilitaries,

the Other Campaign,

women

Thursday, August 12, 2010

Federal Police Riot in Ciudad Juarez Over Corruption

by Kristin Bricker

On August 8, Federal Police stationed in Ciudad Juarez (dubbed the "Murder Capital of the World") staged a thirteen-hour work stoppage to demand the dismissal of their superiors. They claimed their superiors were corrupt: they plant drugs and weapons on suspects, they are members of organized crime, they use their government-issue armored vehicles (such as the ones donated by the US government under the Merida Initiative) to transport drugs, and they throw whistle-blowing officers in jail. Discontent within the force reached a boiling point when commanding officers brought federal charges against an officer who filed a complaint against his superiors for abuse of authority, mistreatment, and death threats.

In response to the arrest of the whistle-blower, approximately 400 agents blocked streets in Ciudad Juarez to demand his release. Their action led to the dismissal of four commanding officers. However, Federal Police Internal Affairs removed the rioting agents from duty and is investigating them for having "instigated attacks and protests." The commanding officers, on the other hand, are not "under investigation," according to the Attorney General's Office. They're simply being asked to give testimony about the protest in Juárez, not about the corruption charges.

More details are available in the following articles, some of which have been edited for length:

Federal Police Rebel Against Commanding Officers

El Heraldo de Chihuahua

Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua (OEM-Informex).- About 400 Federal Police rebelled over mistreatment by their superiors, and they hit the streets to shed light on all of the abuses, cheating, and shady dealings that superiors commit against agents, which include planting drugs and weapons on them in order to frame them, detain them, and charge them with crimes.

[...]

The situation heated up the day before, when agent Victor Manuel de Cid went to the Federal Attorney General's Office (PGR) to file a complaint against superior officers Salomón Alarcón Romero, Joel Ortega, and Ricardo Duque Chávez. He accused them of abuse of authority, mistreatment, and death threats.

Twenty-four hours later, the "snitch" was brought before authorities from the PGR because they supposedly found a weapon and drugs on him. The PGR says it detained him outside the Hotel La Playa, where about 1,200 Federal Police officers are staying. However, his co-workers say they took him out of his room in handcuffs.

[...]

They claimed that a weapon and drugs were planted on their co-worker, and that before he was brought before the PGR, they beat and handcuffed him.

Federal Police Riot Wins Dismissal of Commanders

The Public Security Ministry Says That It Will Investigate Them for Corruption; Agents Accuse Them of Ties to Organized Crime

by Rubén Villalpando, La Jornada

The Public Security Ministry removed four "second-level" commanders from their duties in the Federal Police who participated in Operation Chihuahua after dozens of agents denounced various acts of corruption committed by their superiors.

The federal agency announced that the commanders were transferred to Mexico City to be investigated for illegal activities in the line of duty and, "if appropriate, hold them responsible."

The Federal Police's Internal Affairs Division is aware of the complaints and will determine if it will proceed with disciplinary measures against the four commanders.

Yesterday, about 400 Federal Police agents stationed in Juárez refused to work for 13 hours in order to demand the release of a co-worker, whom their superiors accuse of federal crimes, and to demand the dismissal of their commanders, whom they accuse of having ties to organized crime and sending the police to the streets to extort money from people.

Since 4 a.m. hundreds of agents, armed and in uniform, blocked López Mateos Ave. in front of the La Playa Hotel, where they are staying, and demanded the dismissal of their superiors Salomón Alarcón Romero, Joel Ortega, and Ricardo Duque Chávez, who were holed up in rooms 105, 106, and 107 accompanied by 30 mid-level commanders who were trying to protect them.

Between yelling and gun-pointing, the agents burst into their commanders' room, removed Alarcón Olvera, and detained him while they protested. "We went in and we found drugs such as cocaine, marijuana, and weapons that they use to plant on innocent victims," said one. There were also voodoo, black magic, and witchcraft symbols, they said.

The police exchanged harsh words, shoves, kicks, and beatings with the group that was defending the commanders. The insubordinate police explained that Alarcón Olvera planted drugs on one of their co-workers, identified as José D'Cid, who was detained and charged with federal crimes for having filed a complaint against his commanding officer.

During the revolt, the rioters detained a man that attempted to flee out the back of the hotel by knocking out the bars on his window. They found packages that appeared to be full of drugs in his possession.

This man identified himself in front of the media as Julián González, and he said that for the past two weeks he's been in charge of Commander Alarcón Olvera's security. He said that he had gone out to look for a taxi for his boss.

Alarcón Olvera maintained that room 105, where the drugs were found, is not his room, and that "he who doesn't owe anything doesn't fear anything." He commented that he considered the protesters' actions to be illegal. The "subversive" group, he said, is comprised of approximately 25 agents and that they were protesting for the release of an agent who was detained for possessing marijuana.

The agents shouted chants and demanded the presence of the Federal Police Commissioner, Facundo Rosas Rosas. A commission of commanders went to the La Playa to negotiate and reestablish order.

Afterwards, the protesters announced that a solution to the problem was reached which was "favorable to us, above all regarding the detention of an agent on whom they allegedly found drugs." The lanes of López Mateos Ave. were re-opened to traffic.

"Our Commanders are Pure Trash"

One Appears on a List of Drug Cartel Employees, They Say

by Rubén Villalpando, La Jornada

Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, August 8. Agents who participated in this past Saturday's riot made public that their immediate superior, Rodolfo Salomón Alarcón Romero aka El Chamán, lacks rank in the Federal Police and heads up the Juárez force despite the fact that his name appears in a "narcolist"* found by the military last year in Sinaloa.

El Chamán only arrived in Ciudad Juárez this past July, but he was already organizing noisy parties that lasted until dawn, with prostitutes and people who arrived in luxury vehicles. He also had a King Ranch Special Edition pick-up truck that he parked in the entrance to the Hotel La Playa, said the agents.

"The commanders use the armored vehicles to store drugs that they plant on detainees." Another commander, Joel Ortega Montenegro, appears in a list of commanders who are on the Sinaloa cartel's payroll, they claimed.

"Our superiors are pure trash. They report a lot of arrests because they are in cahoots with the prosecutors in the Federal Attorney General's Office (PGR). They capture innocent people and plant drugs on them so that those people pay them big bribes," they said just before the accused were brought to the airport in civilian clothing and transferred by plane to Mexico City amongst strong protests.

This Sunday a painting appeared that said that the man whose dismembered body was found in the Palacio de Mitla shopping mall is a federal police officer who collaborated with Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán.

The agents who arrived on the scene confirmed that the victim was one of their co-workers, but the Assistant Attorney General's Office didn't mention this detail. It only said that "they removed his hands, feet, head, legs, and arms, and they tossed them into the establishment."

This year, 78 police have already died in Ciudad Juárez, twenty of them were Federal Police. That number is higher than the total number of police murdered in 2008 and 2009, according to official government statistics.

Translator's Note:

* "Narcolists" are often found in notebooks during government raids on drug cartels. They supposedly contain the names and ranks of police officers, soldiers, and government officials who are on the cartel payrolls.

Rioting Federal Police Are Removed from Duty and Investigated

by Alejandro Páez, La Crónica de Hoy

Federal Police responsible for a row this past Saturday in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, have been removed from duty and put under investigation for being instigators of the attacks and protests against some of their commanders, whom they accuse of corruption, according to the head of the force's Internal Affairs Division, Marco Tulio López Escamilla.

In a press conference, the Public Security Ministry official explained that his department had already gathered evidence against this group of federal police, and that it would proceed against them if it is proven that they did not comply with department policy.

López Escamilla did not specify the number of agents who were under investigation, but he did say that the four commanders of the Federal Police's Third Contingent who were dismissed were handed over to the Federal Attorney General's Office this past Sunday for alleged corruption and abuse of authority.

The Public Security official said that the events and the subsequent dismissal of the commanders would not affect the operation that the Federal Police have implemented in Juárez since April 8. He pointed out that 5,000 agents participate in the operation.

Likewise, he said that this year 500 complaints have been filed against the Federal Police in Mexico for alleged acts of corruption and irregularities, and that they are being investigated.

No Charges Brought Against Juárez Commanders

by Notimex

The Federal Attorney General's Office (PGR) has announced that the four Federal Police Commanders in Ciudad Juárez who were accused of corruption by two hundred agents are not being detained, nor have charges been filed against them. They are just at the Public Security Ministry's disposition.

Mexico City, Mexico, August 11, 2010.- The Federal Attorney General's Office (PGR) has still not investigated the four Federal Police commanders who were fired in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, after being accused by their subordinates of alleged acts of corruption.

Sources within the agency said that Salomón Alarcón Romero, Joel Ortega Montenegro, Antelmo Casteñada Silva, and Ricardo Duque Chávez only made statements before an agent from the Federal Prosecutor's Office.

This occurred in Federal Police headquarters, located in Iztapalapa, where they gave details about the protest carried out by their subordinates this past Saturday in front of the Hotel La Playa in Ciudad Juárez.

In the PGR there is no preliminary investigation against the four commanders, due to the fact that they have not been turned over to the PGR as detainees nor as persons of interest. Therefore they remain in the police headquarters in the custody of the federal Public Security Ministry [the Ministry that is responsible for the Federal Police].

[...]

On August 8, Federal Police stationed in Ciudad Juarez (dubbed the "Murder Capital of the World") staged a thirteen-hour work stoppage to demand the dismissal of their superiors. They claimed their superiors were corrupt: they plant drugs and weapons on suspects, they are members of organized crime, they use their government-issue armored vehicles (such as the ones donated by the US government under the Merida Initiative) to transport drugs, and they throw whistle-blowing officers in jail. Discontent within the force reached a boiling point when commanding officers brought federal charges against an officer who filed a complaint against his superiors for abuse of authority, mistreatment, and death threats.

In response to the arrest of the whistle-blower, approximately 400 agents blocked streets in Ciudad Juarez to demand his release. Their action led to the dismissal of four commanding officers. However, Federal Police Internal Affairs removed the rioting agents from duty and is investigating them for having "instigated attacks and protests." The commanding officers, on the other hand, are not "under investigation," according to the Attorney General's Office. They're simply being asked to give testimony about the protest in Juárez, not about the corruption charges.

More details are available in the following articles, some of which have been edited for length:

Federal Police Rebel Against Commanding Officers

El Heraldo de Chihuahua

Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua (OEM-Informex).- About 400 Federal Police rebelled over mistreatment by their superiors, and they hit the streets to shed light on all of the abuses, cheating, and shady dealings that superiors commit against agents, which include planting drugs and weapons on them in order to frame them, detain them, and charge them with crimes.

[...]

The situation heated up the day before, when agent Victor Manuel de Cid went to the Federal Attorney General's Office (PGR) to file a complaint against superior officers Salomón Alarcón Romero, Joel Ortega, and Ricardo Duque Chávez. He accused them of abuse of authority, mistreatment, and death threats.

Twenty-four hours later, the "snitch" was brought before authorities from the PGR because they supposedly found a weapon and drugs on him. The PGR says it detained him outside the Hotel La Playa, where about 1,200 Federal Police officers are staying. However, his co-workers say they took him out of his room in handcuffs.

[...]

They claimed that a weapon and drugs were planted on their co-worker, and that before he was brought before the PGR, they beat and handcuffed him.

Federal Police Riot Wins Dismissal of Commanders

The Public Security Ministry Says That It Will Investigate Them for Corruption; Agents Accuse Them of Ties to Organized Crime

by Rubén Villalpando, La Jornada

The Public Security Ministry removed four "second-level" commanders from their duties in the Federal Police who participated in Operation Chihuahua after dozens of agents denounced various acts of corruption committed by their superiors.

The federal agency announced that the commanders were transferred to Mexico City to be investigated for illegal activities in the line of duty and, "if appropriate, hold them responsible."

The Federal Police's Internal Affairs Division is aware of the complaints and will determine if it will proceed with disciplinary measures against the four commanders.

Yesterday, about 400 Federal Police agents stationed in Juárez refused to work for 13 hours in order to demand the release of a co-worker, whom their superiors accuse of federal crimes, and to demand the dismissal of their commanders, whom they accuse of having ties to organized crime and sending the police to the streets to extort money from people.

Since 4 a.m. hundreds of agents, armed and in uniform, blocked López Mateos Ave. in front of the La Playa Hotel, where they are staying, and demanded the dismissal of their superiors Salomón Alarcón Romero, Joel Ortega, and Ricardo Duque Chávez, who were holed up in rooms 105, 106, and 107 accompanied by 30 mid-level commanders who were trying to protect them.

Between yelling and gun-pointing, the agents burst into their commanders' room, removed Alarcón Olvera, and detained him while they protested. "We went in and we found drugs such as cocaine, marijuana, and weapons that they use to plant on innocent victims," said one. There were also voodoo, black magic, and witchcraft symbols, they said.

The police exchanged harsh words, shoves, kicks, and beatings with the group that was defending the commanders. The insubordinate police explained that Alarcón Olvera planted drugs on one of their co-workers, identified as José D'Cid, who was detained and charged with federal crimes for having filed a complaint against his commanding officer.

During the revolt, the rioters detained a man that attempted to flee out the back of the hotel by knocking out the bars on his window. They found packages that appeared to be full of drugs in his possession.

This man identified himself in front of the media as Julián González, and he said that for the past two weeks he's been in charge of Commander Alarcón Olvera's security. He said that he had gone out to look for a taxi for his boss.

Alarcón Olvera maintained that room 105, where the drugs were found, is not his room, and that "he who doesn't owe anything doesn't fear anything." He commented that he considered the protesters' actions to be illegal. The "subversive" group, he said, is comprised of approximately 25 agents and that they were protesting for the release of an agent who was detained for possessing marijuana.

The agents shouted chants and demanded the presence of the Federal Police Commissioner, Facundo Rosas Rosas. A commission of commanders went to the La Playa to negotiate and reestablish order.

Afterwards, the protesters announced that a solution to the problem was reached which was "favorable to us, above all regarding the detention of an agent on whom they allegedly found drugs." The lanes of López Mateos Ave. were re-opened to traffic.

"Our Commanders are Pure Trash"

One Appears on a List of Drug Cartel Employees, They Say

by Rubén Villalpando, La Jornada

Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, August 8. Agents who participated in this past Saturday's riot made public that their immediate superior, Rodolfo Salomón Alarcón Romero aka El Chamán, lacks rank in the Federal Police and heads up the Juárez force despite the fact that his name appears in a "narcolist"* found by the military last year in Sinaloa.

El Chamán only arrived in Ciudad Juárez this past July, but he was already organizing noisy parties that lasted until dawn, with prostitutes and people who arrived in luxury vehicles. He also had a King Ranch Special Edition pick-up truck that he parked in the entrance to the Hotel La Playa, said the agents.

"The commanders use the armored vehicles to store drugs that they plant on detainees." Another commander, Joel Ortega Montenegro, appears in a list of commanders who are on the Sinaloa cartel's payroll, they claimed.

"Our superiors are pure trash. They report a lot of arrests because they are in cahoots with the prosecutors in the Federal Attorney General's Office (PGR). They capture innocent people and plant drugs on them so that those people pay them big bribes," they said just before the accused were brought to the airport in civilian clothing and transferred by plane to Mexico City amongst strong protests.

This Sunday a painting appeared that said that the man whose dismembered body was found in the Palacio de Mitla shopping mall is a federal police officer who collaborated with Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán.

The agents who arrived on the scene confirmed that the victim was one of their co-workers, but the Assistant Attorney General's Office didn't mention this detail. It only said that "they removed his hands, feet, head, legs, and arms, and they tossed them into the establishment."

This year, 78 police have already died in Ciudad Juárez, twenty of them were Federal Police. That number is higher than the total number of police murdered in 2008 and 2009, according to official government statistics.

Translator's Note:

* "Narcolists" are often found in notebooks during government raids on drug cartels. They supposedly contain the names and ranks of police officers, soldiers, and government officials who are on the cartel payrolls.

Rioting Federal Police Are Removed from Duty and Investigated

by Alejandro Páez, La Crónica de Hoy

Federal Police responsible for a row this past Saturday in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, have been removed from duty and put under investigation for being instigators of the attacks and protests against some of their commanders, whom they accuse of corruption, according to the head of the force's Internal Affairs Division, Marco Tulio López Escamilla.

In a press conference, the Public Security Ministry official explained that his department had already gathered evidence against this group of federal police, and that it would proceed against them if it is proven that they did not comply with department policy.

López Escamilla did not specify the number of agents who were under investigation, but he did say that the four commanders of the Federal Police's Third Contingent who were dismissed were handed over to the Federal Attorney General's Office this past Sunday for alleged corruption and abuse of authority.

The Public Security official said that the events and the subsequent dismissal of the commanders would not affect the operation that the Federal Police have implemented in Juárez since April 8. He pointed out that 5,000 agents participate in the operation.

Likewise, he said that this year 500 complaints have been filed against the Federal Police in Mexico for alleged acts of corruption and irregularities, and that they are being investigated.

No Charges Brought Against Juárez Commanders

by Notimex

The Federal Attorney General's Office (PGR) has announced that the four Federal Police Commanders in Ciudad Juárez who were accused of corruption by two hundred agents are not being detained, nor have charges been filed against them. They are just at the Public Security Ministry's disposition.

Mexico City, Mexico, August 11, 2010.- The Federal Attorney General's Office (PGR) has still not investigated the four Federal Police commanders who were fired in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, after being accused by their subordinates of alleged acts of corruption.

Sources within the agency said that Salomón Alarcón Romero, Joel Ortega Montenegro, Antelmo Casteñada Silva, and Ricardo Duque Chávez only made statements before an agent from the Federal Prosecutor's Office.

This occurred in Federal Police headquarters, located in Iztapalapa, where they gave details about the protest carried out by their subordinates this past Saturday in front of the Hotel La Playa in Ciudad Juárez.

In the PGR there is no preliminary investigation against the four commanders, due to the fact that they have not been turned over to the PGR as detainees nor as persons of interest. Therefore they remain in the police headquarters in the custody of the federal Public Security Ministry [the Ministry that is responsible for the Federal Police].

[...]

Wednesday, August 11, 2010

Triqui Women Prepare For Third Peace Caravan to Mexico City

Faced with Silence in Oaxaca, They Request That Paramilitaries Be Dismantled

by Gladis Torres Ruiz, CIMAC Noticias

Mexico City, August 9, 2010 (CIMAC).- Women in resistance from the autonomous municipality of San Juan Copala, Oaxaca, announced that, faced with the constant danger of being beaten, murdered, or sexually abused, they are preparing the "Third Peace Caravan," which will depart from Huajuapan de León and end in Mexico City.

In a press conference, Hilda Sánchez Gutiérrez and Josefina Albino Ortiz, coordinators of the autonomous municipality of San Juan Copala, said that women from their community have been disappeared, beaten, raped, and murdered by men who belong to the Union for the Social Well-being of the Triqui Region (UBISORT). [1]

In San Juan Copala, the Triqui people have a long history of struggle for indigenous peoples' right to self-determination. However, a decades-long social conflict has caused internal division.

For months, San Juan Copala has been under siege by paramilitary groups who, according to autonomous authorities and social organizations, act with the Oaxacan government's complicity.

"That is why today we don't want to remain silent. We want to publicly denounce that as women we are most affected by this violent situation, by isolation and lack of basic services such as education and food supplies. We are the ones who remain in the community," said Sánchez Gutiérrez.

She said that in order to survive, the women must risk their lives walking along paths in order to get to other communities in order to buy some basic goods and "when we return [to San Juan Copala] we run the risk that they will rob us or rape us or kill us."

Women have lived with this grave violence for years in San Juan Copala. "We just want to live in peace and we want our rights as indigenous people to be respected--[rights such as] self-determination and and the right to live without violence," they added.

They mentioned that this past Friday they met with the United Nations Assistant High Commissioner for Human Rights, Kyung-wha Kang. They informed her of the constant human rights violations, said Sánchez Gutiérrez.

She said that the High Commissioner was very attentive and expressed to them that impunity is one of the factors that encourages crime and violence. She told them that the only thing that can guarantee that human rights are respected is justice, and she requested that they document their community's situation in order to more deeply understand the problem.

In the name of the women in resistance in her community, Sánchez Gutiérrez denounced that men from UBISORT have been responsible for all of the attacks on Triqui women, and that for that reason they hold them [UBISORT] responsible for anything that happens to them, because they [UBISORT] always reacts violently when people denounce them.

"Above all, it is because they don't consider women to be human beings. They humiliate us, they don't take our opinion into account, and we are the ones who pay for their thirst for vengeance and for the hatred that they feel towards women," said the young indigenous woman.

Recent Attacks

Accompanied by six indigenous women with their daughters and sons, Sánchez Gutiérrez recounted that this past May 15, two differently abled women were attacked, beaten, and dragged during a kidnapping attempt perpetrated by UBISORT leaders Rufino and Anastasio Juárez, who were drunk.[2]

That same day, 30 women who were returning to San Juan Copala after collecting their aid from the Opportunities Program [a government welfare program] had their supplies stolen. Nine women, two children, and a baby were detained for over twelve hours by members of the UBISORT group.

On May 20, Cleriberta Castro Aguilar was murdered along with her husband. On June 24, 8-year-old Miriam Martínez was wounded during a shooting perpetrated by the armed group. On June 26, the municipality was attacked and Marcelina de Jesús López and Celestina Cruz Ramírez were wounded, added Sánchez Gutiérrez.

Third Caravan

In support of the autonomous municipality, she said, on August 23 the "Third Peace Caravan" will leave from Huajuapan de León, Oaxaca, for Mexico City. It will be led by women and their daughters and sons.

She said that the Caravan plans to stop in the community where human rights defender Beatriz Alberta Cariño lived. Cariño was murdered this past April 27 during an armed attack on the International Human Rights Observation Caravan, which was headed to San Juan Copala.

The delivery of humanitarian aid to the town of San Juan Copala has been thwarted on two occasions, most recently on June 8, when [the second caravan] attempted to deliver over 30 tons of supplies that were left in a warehouse in Huajuapan de León.

Faced with that situation, the supplies had to be transported by residents in an "Operation Ant." To date, 70% of the aid has been carried into San Juan Copala on the backs of residents of the Triqui community.

Hilda Sánchez added that the caravan also plans to make a stop in San Salvador Atenco.

The goal is to demand that the federal government dismantle paramilitary groups and that peace return to the municipality, because the Oaxacan government has not listened to them. They will also visit government offices such as the Secretary of the Interior and the Federal Attorney General's Office.

Translated by Kristin Bricker.

Translator's Notes:

[1] The United Nations High Commission on Refugees classifies UBISORT, which was founded by the ruling political party in Oaxaca, as a paramilitary organization.

[2] Anastasio Juárez was murdered last week, leading to a joint raid on San Juan Copala carried out by UBISORT and Oaxacan state police. State police have since left the community, but the paramilitaries have taken over San Juan Copala's town hall and the military has deployed to the paramiltary-controlled town of La Sabana, located 5-10 minutes from San Juan Copala.

by Gladis Torres Ruiz, CIMAC Noticias

Mexico City, August 9, 2010 (CIMAC).- Women in resistance from the autonomous municipality of San Juan Copala, Oaxaca, announced that, faced with the constant danger of being beaten, murdered, or sexually abused, they are preparing the "Third Peace Caravan," which will depart from Huajuapan de León and end in Mexico City.

In a press conference, Hilda Sánchez Gutiérrez and Josefina Albino Ortiz, coordinators of the autonomous municipality of San Juan Copala, said that women from their community have been disappeared, beaten, raped, and murdered by men who belong to the Union for the Social Well-being of the Triqui Region (UBISORT). [1]

In San Juan Copala, the Triqui people have a long history of struggle for indigenous peoples' right to self-determination. However, a decades-long social conflict has caused internal division.

For months, San Juan Copala has been under siege by paramilitary groups who, according to autonomous authorities and social organizations, act with the Oaxacan government's complicity.

"That is why today we don't want to remain silent. We want to publicly denounce that as women we are most affected by this violent situation, by isolation and lack of basic services such as education and food supplies. We are the ones who remain in the community," said Sánchez Gutiérrez.

She said that in order to survive, the women must risk their lives walking along paths in order to get to other communities in order to buy some basic goods and "when we return [to San Juan Copala] we run the risk that they will rob us or rape us or kill us."

Women have lived with this grave violence for years in San Juan Copala. "We just want to live in peace and we want our rights as indigenous people to be respected--[rights such as] self-determination and and the right to live without violence," they added.

They mentioned that this past Friday they met with the United Nations Assistant High Commissioner for Human Rights, Kyung-wha Kang. They informed her of the constant human rights violations, said Sánchez Gutiérrez.

She said that the High Commissioner was very attentive and expressed to them that impunity is one of the factors that encourages crime and violence. She told them that the only thing that can guarantee that human rights are respected is justice, and she requested that they document their community's situation in order to more deeply understand the problem.

In the name of the women in resistance in her community, Sánchez Gutiérrez denounced that men from UBISORT have been responsible for all of the attacks on Triqui women, and that for that reason they hold them [UBISORT] responsible for anything that happens to them, because they [UBISORT] always reacts violently when people denounce them.

"Above all, it is because they don't consider women to be human beings. They humiliate us, they don't take our opinion into account, and we are the ones who pay for their thirst for vengeance and for the hatred that they feel towards women," said the young indigenous woman.

Recent Attacks

Accompanied by six indigenous women with their daughters and sons, Sánchez Gutiérrez recounted that this past May 15, two differently abled women were attacked, beaten, and dragged during a kidnapping attempt perpetrated by UBISORT leaders Rufino and Anastasio Juárez, who were drunk.[2]

That same day, 30 women who were returning to San Juan Copala after collecting their aid from the Opportunities Program [a government welfare program] had their supplies stolen. Nine women, two children, and a baby were detained for over twelve hours by members of the UBISORT group.

On May 20, Cleriberta Castro Aguilar was murdered along with her husband. On June 24, 8-year-old Miriam Martínez was wounded during a shooting perpetrated by the armed group. On June 26, the municipality was attacked and Marcelina de Jesús López and Celestina Cruz Ramírez were wounded, added Sánchez Gutiérrez.

Third Caravan

In support of the autonomous municipality, she said, on August 23 the "Third Peace Caravan" will leave from Huajuapan de León, Oaxaca, for Mexico City. It will be led by women and their daughters and sons.

She said that the Caravan plans to stop in the community where human rights defender Beatriz Alberta Cariño lived. Cariño was murdered this past April 27 during an armed attack on the International Human Rights Observation Caravan, which was headed to San Juan Copala.

The delivery of humanitarian aid to the town of San Juan Copala has been thwarted on two occasions, most recently on June 8, when [the second caravan] attempted to deliver over 30 tons of supplies that were left in a warehouse in Huajuapan de León.

Faced with that situation, the supplies had to be transported by residents in an "Operation Ant." To date, 70% of the aid has been carried into San Juan Copala on the backs of residents of the Triqui community.

Hilda Sánchez added that the caravan also plans to make a stop in San Salvador Atenco.

The goal is to demand that the federal government dismantle paramilitary groups and that peace return to the municipality, because the Oaxacan government has not listened to them. They will also visit government offices such as the Secretary of the Interior and the Federal Attorney General's Office.

Translated by Kristin Bricker.

Translator's Notes:

[1] The United Nations High Commission on Refugees classifies UBISORT, which was founded by the ruling political party in Oaxaca, as a paramilitary organization.

[2] Anastasio Juárez was murdered last week, leading to a joint raid on San Juan Copala carried out by UBISORT and Oaxacan state police. State police have since left the community, but the paramilitaries have taken over San Juan Copala's town hall and the military has deployed to the paramiltary-controlled town of La Sabana, located 5-10 minutes from San Juan Copala.

Oscar Olivera: Opposition in Times of Evo

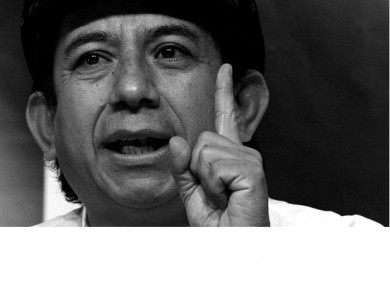

Interview by Matteo Dean, Desinformémonos

In this interview, the prominent Bolivian leader—who prefers to be defined as an “ex-labor leader and social activist”—explains his critical position towards Evo Morales’ government, the contradictions and dangers that are seen in Bolivia now, and the perspectives of the labor and autonomous movements.

The Fragmentation of the Movement: “You’re With Us or Against Us”

In Bolivia's government, discourse and practice are completely diverging. Individualism is encouraged and community decision-making is penalized. Social movements are almost entirely subordinated to the government. The saying “you are with us or against us” is in full effect. But moreover, it’s not just that they ignore you or you don’t exist like it was not too long ago. No, now, after the last elections, the government seems to say, “Yes, you exist, and I will annihilate you so that you won’t exist anymore.” So there’s a strong smear and slander campaign, very low, very destructive, against some of the union or social leaders who have taken a strongly autonomous position.

I believe that there are different factors. On the one hand, there is a general attitude, and on the other there is the presence of media officials in the government who operate these types of policies. When Evo Morales took office, I was worried because of the type of person he is. In the end, he is a person who has his legitimate objectives. For example, he always wanted to be president. Evo was one of the supporters of the gas referendum in 2004. Many of us were against it because we considered the consultation to be a trick. He didn’t; he negotiated with the government at that time, all so that he could become a part of that very government.

I believe that on that occasion, Evo used the people. It doesn’t seem to me to be very honest or loyal, that he has always used his characteristic ability to seduce in order to attract people, use them, and later toss them aside, sometimes in a bad way. He is a leader and here there is no horizontality of power; there’s not even the most minimal attempt to offer power to the people. Here, power is concentrated in one person, and that person is Evo Morales. He decides everything; he even approves the mayoral candidates in this country.

Moreover, he has surrounded himself with people who are very differential complacent with him, something that he enjoys very much. I saw servile attitudes towards the president. It doesn’t matter what sort of a past said person has if now what that president says is good. One the other hand, a compañero who has never sold out, who has never subordinated himself to anyone, or a sector that was rebellious, that has always been autonomous, that is not tolerated. I believe that it is a mix of personal attitude combined with a network of hotshot personalities who are absolutely unqualified to be there in the government.

For example, I can no longer communicate with him. The last time was two years ago, and now they don’t even communicate with me. It seems as though I am off-limits in the government. And it seems as though the only way to tell him that here we are, insisting, we are still here, aren’t the public letters we send him or the messages that we sent through other people; it’s through mobilizations. For example, in April 2010 the government organized an event to mark ten years since the “water war.” It was a political party event. Five hundred people attended, and it was made clear that the gains that were made ten years ago were one group or sector’s achievement.

A few days later we organized a march that over 10,000 people attended, and we argue that it wasn’t just one group that won, it was the result of collective construction, of a very strong social fabric, very generous, very transparent, and without discrimination of any kind. All of that doesn’t exist anymore. There was a lot of fragmentation and cooptation by the government. And all of us who didn’t want to play that game were subjected to smear campaigns.

I believe that the people who are inside the apparatus fear power from below. When we mobilized, they got scared because they saw that the grassroots was protesting. It was the same grassroots that brought Morales to the presidency, that same grassroots that first mobilized in the “water war.” Foreign Minister David Choquehuanca, whom I have never seen in a single battle anywhere, took the luxury of discrediting the march, saying it was an ultra-rightwing march.

It is disrespectful and it outrages me that an official who was never brave enough to meet with us face-to-face was allowed to discredit us. Moreover, if you take into account that the MAS [Evo Morels’ party] lost in urban zones, they should be trying to get closer to these people, this grassroots who voted for them but marched with us. There is a complete blindness, an arrogant disregard for their own people.

Labor Politics in Bolivia

The project of reforming the labor code in Bolivia—proposed on May 1, 2009—has two big burdens for workers. The first has to do with the criminalization of strikes, of protest. There are new rules that are introduced, such as, for example, that whatever measure the union takes must have a two-thirds majority; under the current regulations 50% plus one is sufficient. Moreover, it is proposed that, in the event of a strike, the workers who do not agree and who want to work can do so.

In the event that a union leader or another worker attempts to stop a strikebreaker, and s/he threatens attacks him, be it verbally or physically, criminal charges can be brought against that person. On the other hand, the proposal strips all public sector workers of their right to strike. That means that all of the water, electrical, telephone, communications, health, and administrative workers will not be able to strike. In this way, union solidarity and the possibility of solidarity actions are under attack.

These proposals reflect an individualistic vision of the worker. We want to maintain the collective vision, where unions represent the workers in an organized manner. We have here a precise ideology that is infiltrating itself inside the government through the technocrats. For example, the new anti-corruption law that was passed a little while ago introduces snitching as a method. That is, individualism—distrust in others instead of collectivism and community—continues to be encouraged.

There is not an official discourse that promotes these proposals. I believe that there are people inside who have slipped into the government. They are interested in getting money and financial resources so that there is macroeconomic stability. The working world, just like the water, doesn’t matter to them. In the same way, the people’s daily life doesn’t interest them. In many social sectors, after five years of this government’s management, not only have things not changed, they’ve gotten worse.

We are doing two things at this point in time. The first is the ideological struggle against the government, against individualism and snitching, against the criminalization of protest, because what not even the military governments were able to do, this government is doing. There are people who have inserted themselves in the government and, in a very underground manner, are negotiating with economic powers, with businessmen. The labor project must have been developed with employers; there’s no other explication. But because Evo Morales has a very strong image, one thinks that everything he does is good.

The second is to try to resist and conserve the little that has remained of the general labor law that is over sixty years old which, yes, has turned into something contradictory and disordered, but that doesn’t mean they can impose a regressive law like the new project. For example: this law (the government’s proposal) legalizes outsourcing. Now, on the production lines, the employees and the subcontractors work side-by-side. Until words separate you, divide you, fragment you, and discriminate against you.

The Community and the Union

However, we have ancestral roots that refer to the concept of community. This culture of feeling and acting as a community is being lost, and we want to save it. From our perspective, the union can be an urban replica of a community, that is, that no one can fragment or divide us, that decisions are made collectively and by consensus, that there must be rotating responsibilities, that a position can be revoked: in short, how things work in Andean communities.

Urban Sprawl, Corruption, and Drug Trafficking in Cochabamba

In Cochabamba there are three problems. The first is a process of very fast urban sprawl. The State has established that land and soil are a business. The absolutely criminal activity of urbanizing everything is being encouraged: farmland, forestry development parks, etc. All of this is related to the issue of water. In the city there are about ten thousand wells that are fed by the waters that flow down from the mountains. Now those wells are drying up, they have very low water levels, which requires deeper drilling. Faced with this situation, there is no one to stop it because it is all being promoted by both the national and local government.

The second problem is the issue of corruption. Because institutionalized corruption has not changed, many compañeros who went to “change the state,” “horizontalize” power, or create a “participatory institutions that are open to the people” have let themselves be transformed by the state and they have become corrupt. An example is the case of the man who was going to be Evo Morales’ successor and is now in prison: Santos Ramírez Valverde[1].

The third issue is the drug trafficking that is threatening communities here in Cochabamba. It is paradoxical, because when the US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) was here, the problem was more controlled. This is a very serious issue that will have to be faced, because there are sectors of coca leaf producers who are getting involved in drug trafficking. If it goes on like this, it could mean that the coca leaf that brought Morales into the government will be the very thing that removes him from it.

Anti-capitalist Discourse and Inconsistent Practice

There are many contradictions between the anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist discourse and the sort of capitalist development that is being promoted. The case of the San Cristóbal mine[2] is a good example, as is IIRSA[3]. That is, that which the rightwing could not achieve, the government is now doing together with Lula (the president of Brazil). These contradictions between discourse and concrete action do not permit the government to hide what is going on here. The government says that everything is to get financial resources together for the people’s needs and to establish a degree of balance with nature.

But out there in the communities, where the people are opposed, the government immediately discredits whoever protests or it supplants them with other leaders who are sent by the government. In other cases, the State is completely absent, which leads people to want to solve their problems themselves. It is why during the past five years there have been over sixty murders. It is the case, for example, in Huanuni, where there was a confrontation between the communities that work the mines in cooperatives and the union workers: in October 2006, 4,000 community members, very young people, faced off with union members over a deposit, resulting in 17 deaths.

The Autonomy Movement

It is a very difficult moment for the movement in Bolivia. To start with, there are no spaces for autonomy—not indigenous, not municipal, nothing. There is a strong image of Evo Morales that does not permit the existence of an autonomous voice. But the people are not stupid and they find out that this is not good, even though they wouldn’t dare raise their voices because there is some level of repression.

With this government I view any autonomous space as very difficult. It is paradoxical because this process was pushed forward by the autonomies. No one was telling us what to do. There was a collective deliberation between us and we made things happen. Now this doesn’t happen anymore. We went from autonomy to absolute subordination.

With respect to this government, there is a lot of hope here as well as in many parts of the world. The government utilizes a Guevarist, Marxist, anti-imperialist language that leads to relationships that worry me. For example, the relationship between Hugo Chávez of Venezuela, Iranian President Ahmadineyad, and the Bolivian government. Someone should have seen what was going on in those countries before building friendships. For example, in Iran there is very strong repression against the labor movement and against social movements’ autonomies.

I am so pessimistic that I don’t believe that Morales’ government can manage to survive its five-year rule. People are going to become disenchanted to some degree. And old peasant organizer from the 1o de mayo neighborhood, a very poor area, told me: “These MAS (Movement To Socialism, Evo Morales’ party) electoral victories and this hopeful image of the government are the fruit of our efforts; but all of that is being turned into a party for the same rich people as before.”

Despite the fact that we are starting to see some discontent and disenchantment amongst the people, which is reflected in the election results that the government is so interested in, one thing is certain: people feel blackmailed in a way, because if this falls to pieces, the question is: “What happens next”? If this breaks down, that would be a party for the rightwing, who could say to the people, “You’ve had a Marxist, a Guevarist, an Indigenist…and what did they do?” If everything breaks down, we the downtrodden will pay, as always.

Personal and Collective Perspectives

Being indigenous is not a matter of your face, your features, the color of your skin, or your vocabulary. It’s a matter of attitude. The indigenous person is generous and respectful, and is transparent. And this government, even though it might say it is indigenous, does exactly the opposite: it is authoritarian and looks down upon those who don’t think the same as it does. That’s why I didn’t want to take a government position, because I believe that what you experience in your daily life makes you change your vision of things and your attitude.

I’ve been thinking about what to do in this context. I have talked with my compañeros and we’ve discussed what Oscar Olivera, that figure who still has a large social base, should do now. And we’ve decided that I should go in deep. I opted to go deep into that social base and search and establish a new trench for struggle that would allow me to once again submerge myself in the people’s daily life, in their worries, and from there reconstruct a social fabric in case of a possible breakdown [in the government].

I stopped appearing in public spaces (the reference here is to the Mesa 18, which was organized as an “alternative” to the Climate Change Summit organized by the Bolivian government in April of this year). I thought that it would be better to go to the grassroots and work there in what I like: talking with the people, feeling people’s concerns, going to the factories to educate the workers. Perhaps my last public activity was the Water Fair, because public appearances expose me to government defamation campaigns and this begins to wear on me.

I wanted to go back to the factory, but the company didn’t want me. So I stayed here, organizing the labor and popular school. We turned this place (the interview took place in the Cochabamba Manufacturing Complex) into a social center of training, information, organization, and knowledge exchange which is open to everyone, to all workers—new and old, men and women. It’s what we’re trying to build here: a very autonomous and very critical space that has the capacity to prepare people to go to communities, to neighborhoods, and build this autonomy.

All of this is with the perspective of thinking that the solution (to the problems) lies in the people, not in politics as it is conceived and practiced nowadays. Putting our people in state apparatuses doesn’t work at all. It is definitely a deception. The solution is self-management. Here in the city, for example, there are some factories that we want to take over and self-manage. We’ll see.

Translated by Kristin Bricker.

Translator’s Notes:

[1] Santos Ramírez Valverde was president of Bolivia’s state-owned oil company and leader of MAS. He is serving thirteen years in prison for embezzling money from the oil company. His fellow inmates now accuse him of charging them illegal fees to enter the exclusive section of the Bolivian prison where he is serving his sentence.

[2] The San Cristóbal mine has polluted water sources that serve over 10,000 people, according to a report by hydrologist and mining expert Robert Morán. In response to the report, Olivera argued that “the government has a discourse against capitalism and imperialism, but it lets capitalist companies exploit the country’s natural resources.”

[3] IIRSA (Initiative for the Integration of Regional Infrastructure in South America) is a South American regional integration plan initiated by Brazil. IIRSA “promotes the development of transport, energy and communication infrastructure with a regional vision.”

In this interview, the prominent Bolivian leader—who prefers to be defined as an “ex-labor leader and social activist”—explains his critical position towards Evo Morales’ government, the contradictions and dangers that are seen in Bolivia now, and the perspectives of the labor and autonomous movements.

The Fragmentation of the Movement: “You’re With Us or Against Us”

In Bolivia's government, discourse and practice are completely diverging. Individualism is encouraged and community decision-making is penalized. Social movements are almost entirely subordinated to the government. The saying “you are with us or against us” is in full effect. But moreover, it’s not just that they ignore you or you don’t exist like it was not too long ago. No, now, after the last elections, the government seems to say, “Yes, you exist, and I will annihilate you so that you won’t exist anymore.” So there’s a strong smear and slander campaign, very low, very destructive, against some of the union or social leaders who have taken a strongly autonomous position.

I believe that there are different factors. On the one hand, there is a general attitude, and on the other there is the presence of media officials in the government who operate these types of policies. When Evo Morales took office, I was worried because of the type of person he is. In the end, he is a person who has his legitimate objectives. For example, he always wanted to be president. Evo was one of the supporters of the gas referendum in 2004. Many of us were against it because we considered the consultation to be a trick. He didn’t; he negotiated with the government at that time, all so that he could become a part of that very government.

I believe that on that occasion, Evo used the people. It doesn’t seem to me to be very honest or loyal, that he has always used his characteristic ability to seduce in order to attract people, use them, and later toss them aside, sometimes in a bad way. He is a leader and here there is no horizontality of power; there’s not even the most minimal attempt to offer power to the people. Here, power is concentrated in one person, and that person is Evo Morales. He decides everything; he even approves the mayoral candidates in this country.

Moreover, he has surrounded himself with people who are very differential complacent with him, something that he enjoys very much. I saw servile attitudes towards the president. It doesn’t matter what sort of a past said person has if now what that president says is good. One the other hand, a compañero who has never sold out, who has never subordinated himself to anyone, or a sector that was rebellious, that has always been autonomous, that is not tolerated. I believe that it is a mix of personal attitude combined with a network of hotshot personalities who are absolutely unqualified to be there in the government.

For example, I can no longer communicate with him. The last time was two years ago, and now they don’t even communicate with me. It seems as though I am off-limits in the government. And it seems as though the only way to tell him that here we are, insisting, we are still here, aren’t the public letters we send him or the messages that we sent through other people; it’s through mobilizations. For example, in April 2010 the government organized an event to mark ten years since the “water war.” It was a political party event. Five hundred people attended, and it was made clear that the gains that were made ten years ago were one group or sector’s achievement.

A few days later we organized a march that over 10,000 people attended, and we argue that it wasn’t just one group that won, it was the result of collective construction, of a very strong social fabric, very generous, very transparent, and without discrimination of any kind. All of that doesn’t exist anymore. There was a lot of fragmentation and cooptation by the government. And all of us who didn’t want to play that game were subjected to smear campaigns.

I believe that the people who are inside the apparatus fear power from below. When we mobilized, they got scared because they saw that the grassroots was protesting. It was the same grassroots that brought Morales to the presidency, that same grassroots that first mobilized in the “water war.” Foreign Minister David Choquehuanca, whom I have never seen in a single battle anywhere, took the luxury of discrediting the march, saying it was an ultra-rightwing march.

It is disrespectful and it outrages me that an official who was never brave enough to meet with us face-to-face was allowed to discredit us. Moreover, if you take into account that the MAS [Evo Morels’ party] lost in urban zones, they should be trying to get closer to these people, this grassroots who voted for them but marched with us. There is a complete blindness, an arrogant disregard for their own people.

Labor Politics in Bolivia

The project of reforming the labor code in Bolivia—proposed on May 1, 2009—has two big burdens for workers. The first has to do with the criminalization of strikes, of protest. There are new rules that are introduced, such as, for example, that whatever measure the union takes must have a two-thirds majority; under the current regulations 50% plus one is sufficient. Moreover, it is proposed that, in the event of a strike, the workers who do not agree and who want to work can do so.

In the event that a union leader or another worker attempts to stop a strikebreaker, and s/he threatens attacks him, be it verbally or physically, criminal charges can be brought against that person. On the other hand, the proposal strips all public sector workers of their right to strike. That means that all of the water, electrical, telephone, communications, health, and administrative workers will not be able to strike. In this way, union solidarity and the possibility of solidarity actions are under attack.

These proposals reflect an individualistic vision of the worker. We want to maintain the collective vision, where unions represent the workers in an organized manner. We have here a precise ideology that is infiltrating itself inside the government through the technocrats. For example, the new anti-corruption law that was passed a little while ago introduces snitching as a method. That is, individualism—distrust in others instead of collectivism and community—continues to be encouraged.

There is not an official discourse that promotes these proposals. I believe that there are people inside who have slipped into the government. They are interested in getting money and financial resources so that there is macroeconomic stability. The working world, just like the water, doesn’t matter to them. In the same way, the people’s daily life doesn’t interest them. In many social sectors, after five years of this government’s management, not only have things not changed, they’ve gotten worse.

We are doing two things at this point in time. The first is the ideological struggle against the government, against individualism and snitching, against the criminalization of protest, because what not even the military governments were able to do, this government is doing. There are people who have inserted themselves in the government and, in a very underground manner, are negotiating with economic powers, with businessmen. The labor project must have been developed with employers; there’s no other explication. But because Evo Morales has a very strong image, one thinks that everything he does is good.

The second is to try to resist and conserve the little that has remained of the general labor law that is over sixty years old which, yes, has turned into something contradictory and disordered, but that doesn’t mean they can impose a regressive law like the new project. For example: this law (the government’s proposal) legalizes outsourcing. Now, on the production lines, the employees and the subcontractors work side-by-side. Until words separate you, divide you, fragment you, and discriminate against you.

The Community and the Union

However, we have ancestral roots that refer to the concept of community. This culture of feeling and acting as a community is being lost, and we want to save it. From our perspective, the union can be an urban replica of a community, that is, that no one can fragment or divide us, that decisions are made collectively and by consensus, that there must be rotating responsibilities, that a position can be revoked: in short, how things work in Andean communities.

Urban Sprawl, Corruption, and Drug Trafficking in Cochabamba

In Cochabamba there are three problems. The first is a process of very fast urban sprawl. The State has established that land and soil are a business. The absolutely criminal activity of urbanizing everything is being encouraged: farmland, forestry development parks, etc. All of this is related to the issue of water. In the city there are about ten thousand wells that are fed by the waters that flow down from the mountains. Now those wells are drying up, they have very low water levels, which requires deeper drilling. Faced with this situation, there is no one to stop it because it is all being promoted by both the national and local government.

The second problem is the issue of corruption. Because institutionalized corruption has not changed, many compañeros who went to “change the state,” “horizontalize” power, or create a “participatory institutions that are open to the people” have let themselves be transformed by the state and they have become corrupt. An example is the case of the man who was going to be Evo Morales’ successor and is now in prison: Santos Ramírez Valverde[1].

The third issue is the drug trafficking that is threatening communities here in Cochabamba. It is paradoxical, because when the US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) was here, the problem was more controlled. This is a very serious issue that will have to be faced, because there are sectors of coca leaf producers who are getting involved in drug trafficking. If it goes on like this, it could mean that the coca leaf that brought Morales into the government will be the very thing that removes him from it.

Anti-capitalist Discourse and Inconsistent Practice

There are many contradictions between the anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist discourse and the sort of capitalist development that is being promoted. The case of the San Cristóbal mine[2] is a good example, as is IIRSA[3]. That is, that which the rightwing could not achieve, the government is now doing together with Lula (the president of Brazil). These contradictions between discourse and concrete action do not permit the government to hide what is going on here. The government says that everything is to get financial resources together for the people’s needs and to establish a degree of balance with nature.

But out there in the communities, where the people are opposed, the government immediately discredits whoever protests or it supplants them with other leaders who are sent by the government. In other cases, the State is completely absent, which leads people to want to solve their problems themselves. It is why during the past five years there have been over sixty murders. It is the case, for example, in Huanuni, where there was a confrontation between the communities that work the mines in cooperatives and the union workers: in October 2006, 4,000 community members, very young people, faced off with union members over a deposit, resulting in 17 deaths.

The Autonomy Movement

It is a very difficult moment for the movement in Bolivia. To start with, there are no spaces for autonomy—not indigenous, not municipal, nothing. There is a strong image of Evo Morales that does not permit the existence of an autonomous voice. But the people are not stupid and they find out that this is not good, even though they wouldn’t dare raise their voices because there is some level of repression.

With this government I view any autonomous space as very difficult. It is paradoxical because this process was pushed forward by the autonomies. No one was telling us what to do. There was a collective deliberation between us and we made things happen. Now this doesn’t happen anymore. We went from autonomy to absolute subordination.