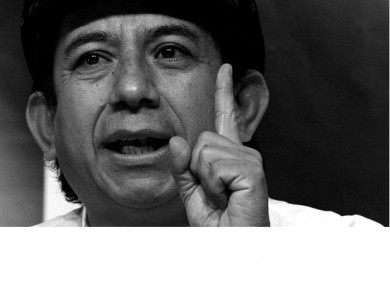

Interview by Matteo Dean, Desinformémonos

In this interview, the prominent Bolivian leader—who prefers to be defined as an “ex-labor leader and social activist”—explains his critical position towards Evo Morales’ government, the contradictions and dangers that are seen in Bolivia now, and the perspectives of the labor and autonomous movements.

The Fragmentation of the Movement: “You’re With Us or Against Us”

In Bolivia's government, discourse and practice are completely diverging. Individualism is encouraged and community decision-making is penalized. Social movements are almost entirely subordinated to the government. The saying “you are with us or against us” is in full effect. But moreover, it’s not just that they ignore you or you don’t exist like it was not too long ago. No, now, after the last elections, the government seems to say, “Yes, you exist, and I will annihilate you so that you won’t exist anymore.” So there’s a strong smear and slander campaign, very low, very destructive, against some of the union or social leaders who have taken a strongly autonomous position.

I believe that there are different factors. On the one hand, there is a general attitude, and on the other there is the presence of media officials in the government who operate these types of policies. When Evo Morales took office, I was worried because of the type of person he is. In the end, he is a person who has his legitimate objectives. For example, he always wanted to be president. Evo was one of the supporters of the gas referendum in 2004. Many of us were against it because we considered the consultation to be a trick. He didn’t; he negotiated with the government at that time, all so that he could become a part of that very government.

I believe that on that occasion, Evo used the people. It doesn’t seem to me to be very honest or loyal, that he has always used his characteristic ability to seduce in order to attract people, use them, and later toss them aside, sometimes in a bad way. He is a leader and here there is no horizontality of power; there’s not even the most minimal attempt to offer power to the people. Here, power is concentrated in one person, and that person is Evo Morales. He decides everything; he even approves the mayoral candidates in this country.

Moreover, he has surrounded himself with people who are very differential complacent with him, something that he enjoys very much. I saw servile attitudes towards the president. It doesn’t matter what sort of a past said person has if now what that president says is good. One the other hand, a compañero who has never sold out, who has never subordinated himself to anyone, or a sector that was rebellious, that has always been autonomous, that is not tolerated. I believe that it is a mix of personal attitude combined with a network of hotshot personalities who are absolutely unqualified to be there in the government.

For example, I can no longer communicate with him. The last time was two years ago, and now they don’t even communicate with me. It seems as though I am off-limits in the government. And it seems as though the only way to tell him that here we are, insisting, we are still here, aren’t the public letters we send him or the messages that we sent through other people; it’s through mobilizations. For example, in April 2010 the government organized an event to mark ten years since the “water war.” It was a political party event. Five hundred people attended, and it was made clear that the gains that were made ten years ago were one group or sector’s achievement.

A few days later we organized a march that over 10,000 people attended, and we argue that it wasn’t just one group that won, it was the result of collective construction, of a very strong social fabric, very generous, very transparent, and without discrimination of any kind. All of that doesn’t exist anymore. There was a lot of fragmentation and cooptation by the government. And all of us who didn’t want to play that game were subjected to smear campaigns.

I believe that the people who are inside the apparatus fear power from below. When we mobilized, they got scared because they saw that the grassroots was protesting. It was the same grassroots that brought Morales to the presidency, that same grassroots that first mobilized in the “water war.” Foreign Minister David Choquehuanca, whom I have never seen in a single battle anywhere, took the luxury of discrediting the march, saying it was an ultra-rightwing march.

It is disrespectful and it outrages me that an official who was never brave enough to meet with us face-to-face was allowed to discredit us. Moreover, if you take into account that the MAS [Evo Morels’ party] lost in urban zones, they should be trying to get closer to these people, this grassroots who voted for them but marched with us. There is a complete blindness, an arrogant disregard for their own people.

Labor Politics in Bolivia

The project of reforming the labor code in Bolivia—proposed on May 1, 2009—has two big burdens for workers. The first has to do with the criminalization of strikes, of protest. There are new rules that are introduced, such as, for example, that whatever measure the union takes must have a two-thirds majority; under the current regulations 50% plus one is sufficient. Moreover, it is proposed that, in the event of a strike, the workers who do not agree and who want to work can do so.

In the event that a union leader or another worker attempts to stop a strikebreaker, and s/he threatens attacks him, be it verbally or physically, criminal charges can be brought against that person. On the other hand, the proposal strips all public sector workers of their right to strike. That means that all of the water, electrical, telephone, communications, health, and administrative workers will not be able to strike. In this way, union solidarity and the possibility of solidarity actions are under attack.

These proposals reflect an individualistic vision of the worker. We want to maintain the collective vision, where unions represent the workers in an organized manner. We have here a precise ideology that is infiltrating itself inside the government through the technocrats. For example, the new anti-corruption law that was passed a little while ago introduces snitching as a method. That is, individualism—distrust in others instead of collectivism and community—continues to be encouraged.

There is not an official discourse that promotes these proposals. I believe that there are people inside who have slipped into the government. They are interested in getting money and financial resources so that there is macroeconomic stability. The working world, just like the water, doesn’t matter to them. In the same way, the people’s daily life doesn’t interest them. In many social sectors, after five years of this government’s management, not only have things not changed, they’ve gotten worse.

We are doing two things at this point in time. The first is the ideological struggle against the government, against individualism and snitching, against the criminalization of protest, because what not even the military governments were able to do, this government is doing. There are people who have inserted themselves in the government and, in a very underground manner, are negotiating with economic powers, with businessmen. The labor project must have been developed with employers; there’s no other explication. But because Evo Morales has a very strong image, one thinks that everything he does is good.

The second is to try to resist and conserve the little that has remained of the general labor law that is over sixty years old which, yes, has turned into something contradictory and disordered, but that doesn’t mean they can impose a regressive law like the new project. For example: this law (the government’s proposal) legalizes outsourcing. Now, on the production lines, the employees and the subcontractors work side-by-side. Until words separate you, divide you, fragment you, and discriminate against you.

The Community and the Union

However, we have ancestral roots that refer to the concept of community. This culture of feeling and acting as a community is being lost, and we want to save it. From our perspective, the union can be an urban replica of a community, that is, that no one can fragment or divide us, that decisions are made collectively and by consensus, that there must be rotating responsibilities, that a position can be revoked: in short, how things work in Andean communities.

Urban Sprawl, Corruption, and Drug Trafficking in Cochabamba

In Cochabamba there are three problems. The first is a process of very fast urban sprawl. The State has established that land and soil are a business. The absolutely criminal activity of urbanizing everything is being encouraged: farmland, forestry development parks, etc. All of this is related to the issue of water. In the city there are about ten thousand wells that are fed by the waters that flow down from the mountains. Now those wells are drying up, they have very low water levels, which requires deeper drilling. Faced with this situation, there is no one to stop it because it is all being promoted by both the national and local government.

The second problem is the issue of corruption. Because institutionalized corruption has not changed, many compañeros who went to “change the state,” “horizontalize” power, or create a “participatory institutions that are open to the people” have let themselves be transformed by the state and they have become corrupt. An example is the case of the man who was going to be Evo Morales’ successor and is now in prison: Santos Ramírez Valverde[1].

The third issue is the drug trafficking that is threatening communities here in Cochabamba. It is paradoxical, because when the US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) was here, the problem was more controlled. This is a very serious issue that will have to be faced, because there are sectors of coca leaf producers who are getting involved in drug trafficking. If it goes on like this, it could mean that the coca leaf that brought Morales into the government will be the very thing that removes him from it.

Anti-capitalist Discourse and Inconsistent Practice

There are many contradictions between the anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist discourse and the sort of capitalist development that is being promoted. The case of the San Cristóbal mine[2] is a good example, as is IIRSA[3]. That is, that which the rightwing could not achieve, the government is now doing together with Lula (the president of Brazil). These contradictions between discourse and concrete action do not permit the government to hide what is going on here. The government says that everything is to get financial resources together for the people’s needs and to establish a degree of balance with nature.

But out there in the communities, where the people are opposed, the government immediately discredits whoever protests or it supplants them with other leaders who are sent by the government. In other cases, the State is completely absent, which leads people to want to solve their problems themselves. It is why during the past five years there have been over sixty murders. It is the case, for example, in Huanuni, where there was a confrontation between the communities that work the mines in cooperatives and the union workers: in October 2006, 4,000 community members, very young people, faced off with union members over a deposit, resulting in 17 deaths.

The Autonomy Movement

It is a very difficult moment for the movement in Bolivia. To start with, there are no spaces for autonomy—not indigenous, not municipal, nothing. There is a strong image of Evo Morales that does not permit the existence of an autonomous voice. But the people are not stupid and they find out that this is not good, even though they wouldn’t dare raise their voices because there is some level of repression.

With this government I view any autonomous space as very difficult. It is paradoxical because this process was pushed forward by the autonomies. No one was telling us what to do. There was a collective deliberation between us and we made things happen. Now this doesn’t happen anymore. We went from autonomy to absolute subordination.

With respect to this government, there is a lot of hope here as well as in many parts of the world. The government utilizes a Guevarist, Marxist, anti-imperialist language that leads to relationships that worry me. For example, the relationship between Hugo Chávez of Venezuela, Iranian President Ahmadineyad, and the Bolivian government. Someone should have seen what was going on in those countries before building friendships. For example, in Iran there is very strong repression against the labor movement and against social movements’ autonomies.

I am so pessimistic that I don’t believe that Morales’ government can manage to survive its five-year rule. People are going to become disenchanted to some degree. And old peasant organizer from the 1o de mayo neighborhood, a very poor area, told me: “These MAS (Movement To Socialism, Evo Morales’ party) electoral victories and this hopeful image of the government are the fruit of our efforts; but all of that is being turned into a party for the same rich people as before.”

Despite the fact that we are starting to see some discontent and disenchantment amongst the people, which is reflected in the election results that the government is so interested in, one thing is certain: people feel blackmailed in a way, because if this falls to pieces, the question is: “What happens next”? If this breaks down, that would be a party for the rightwing, who could say to the people, “You’ve had a Marxist, a Guevarist, an Indigenist…and what did they do?” If everything breaks down, we the downtrodden will pay, as always.

Personal and Collective Perspectives

Being indigenous is not a matter of your face, your features, the color of your skin, or your vocabulary. It’s a matter of attitude. The indigenous person is generous and respectful, and is transparent. And this government, even though it might say it is indigenous, does exactly the opposite: it is authoritarian and looks down upon those who don’t think the same as it does. That’s why I didn’t want to take a government position, because I believe that what you experience in your daily life makes you change your vision of things and your attitude.

I’ve been thinking about what to do in this context. I have talked with my compañeros and we’ve discussed what Oscar Olivera, that figure who still has a large social base, should do now. And we’ve decided that I should go in deep. I opted to go deep into that social base and search and establish a new trench for struggle that would allow me to once again submerge myself in the people’s daily life, in their worries, and from there reconstruct a social fabric in case of a possible breakdown [in the government].

I stopped appearing in public spaces (the reference here is to the Mesa 18, which was organized as an “alternative” to the Climate Change Summit organized by the Bolivian government in April of this year). I thought that it would be better to go to the grassroots and work there in what I like: talking with the people, feeling people’s concerns, going to the factories to educate the workers. Perhaps my last public activity was the Water Fair, because public appearances expose me to government defamation campaigns and this begins to wear on me.

I wanted to go back to the factory, but the company didn’t want me. So I stayed here, organizing the labor and popular school. We turned this place (the interview took place in the Cochabamba Manufacturing Complex) into a social center of training, information, organization, and knowledge exchange which is open to everyone, to all workers—new and old, men and women. It’s what we’re trying to build here: a very autonomous and very critical space that has the capacity to prepare people to go to communities, to neighborhoods, and build this autonomy.

All of this is with the perspective of thinking that the solution (to the problems) lies in the people, not in politics as it is conceived and practiced nowadays. Putting our people in state apparatuses doesn’t work at all. It is definitely a deception. The solution is self-management. Here in the city, for example, there are some factories that we want to take over and self-manage. We’ll see.

Translated by Kristin Bricker.

Translator’s Notes:

[1] Santos Ramírez Valverde was president of Bolivia’s state-owned oil company and leader of MAS. He is serving thirteen years in prison for embezzling money from the oil company. His fellow inmates now accuse him of charging them illegal fees to enter the exclusive section of the Bolivian prison where he is serving his sentence.

[2] The San Cristóbal mine has polluted water sources that serve over 10,000 people, according to a report by hydrologist and mining expert Robert Morán. In response to the report, Olivera argued that “the government has a discourse against capitalism and imperialism, but it lets capitalist companies exploit the country’s natural resources.”

[3] IIRSA (Initiative for the Integration of Regional Infrastructure in South America) is a South American regional integration plan initiated by Brazil. IIRSA “promotes the development of transport, energy and communication infrastructure with a regional vision.”

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Keep this blog alive

Articles Published Elsewhere

- Foreign Policy In Focus: Migrants Demand End to the Violence

- Guatemala Times: Migrants Demand End to the Violence

- TeleSUR: Quién ganó y quién perdió en las Narco Protestas en México

- Rebelion: Plan México: el contexto de la militarización, la violencia relacionada al narcotráfico, y los derechos humanos

- Left Turn: Plan Mexico: Calderon's Endless War

- El Sendero del Peje: Identificada, Empresa que Enseñó Tortura a Policía de León (PDF)

- Por Esto!: Terroristas Torturadores

- CounterPunch: US Contractor Leads Torture Training in Mexico

- The Indypendent: Congress Approves Plan Mexico

- Upping the Anti: Marcos Announces Continental Indigenous Encounter for October 2007

- Znet: From the Coffee Farms of Chiapas to the Shrimp Farms of the Sinaloan Coast, One Common Struggle

- Left Turn: Breaking Ranks: Refusing to Serve in the Occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip

photos

- Chiapas: Molino Utrilla conflict

- Chiapas: Day of the Dead

- Oaxaca: Sally Grace's photos

- Mexico City Hip Hop

- Mexico City: March for Atenco

- Mexico City: MayDay 2008

- Mexico City: Ex-politcal Prisoners from Atenco Protest Sexual Violence

- Chiapas: International Day in Support of Political Prisoners on Hunger Strike

- Oaxaca: Forum for Freedom of the Country's Political Prisoners of Conscience

Links

- CELMRAZ: Zapatista Language School

- El Enemigo Común

- South Notes

- Rebel Imports

- Regeneración Radio

- Angry White Kid

- Friends of Brad Will

- The Indypendent

- Left Turn

- NYC Grassroots Media Coalition

- Red Emma's Bookstore Cafe

- ZNet

- Zapagringo

- Todos Somos Geckos: A Ground-Level View on Colombia Human Rights Movements

- Sweet Awesome Anarchist Research Blog

About Me

BlogCatalog

Subscribe via email

Labels

- APPO (27)

- Atenco (7)

- autonomy (24)

- Baja California (8)

- Beltrán Leyva brothers (13)

- Bolivia (1)

- Brad Will (12)

- Campeche (1)

- Caribbean (1)

- Central America (11)

- Chiapas (68)

- Chihuahua (25)

- Coahuila (5)

- Colombia (4)

- corruption (37)

- Dominican Republic (1)

- Durango (3)

- economy (6)

- Ecuador (2)

- Edo. de Mexico (11)

- education (3)

- elections (3)

- environment (2)

- español (6)

- FNLS (1)

- gangs (2)

- Guanajuato (9)

- Guatemala (2)

- Guerrero (21)

- Gulf cartel (7)

- Haiti (1)

- Hidalgo (4)

- Honduras (7)

- human rights (25)

- immigration (9)

- Jamaica (1)

- journalists under attack (33)

- Juarez cartel (9)

- Kaibiles (2)

- La Familia cartel (4)

- labor (20)

- land and territory (40)

- Los Zetas (16)

- Merida Initiative (81)

- Mesoamerica Project (2)

- Mexico City (34)

- Michoacan (10)

- militarization (43)

- military jurisdiction (2)

- mining (7)

- Morelos (7)

- NAFTA (3)

- Nuevo Leon (12)

- Oaxaca (57)

- paramilitaries (45)

- PEMEX and petroleum (2)

- Peru (1)

- Plan Mexico (80)

- political prisoners (56)

- privatization (10)

- Puebla (5)

- Quintana Roo (2)

- San Luis Potosí (1)

- Security and Prosperity Partnership (7)

- Sinaloa (10)

- Sinaloa cartel (12)

- SME (7)

- Sonora (6)

- South America (1)

- Spain (1)

- Tabasco (6)

- Tamaulipas (8)

- the Other Campaign (63)

- Tijuana cartel (1)

- torture (46)

- translations (82)

- unnatural disasters (1)

- Veracruz (1)

- war on drugs (114)

- women (35)

- Yucatan (1)

- Zapatistas (59)

0 comments:

Post a Comment Anonymously or Using Your Google ID

or Comment Using Facebook, Yahoo!, Hotmail, or AOL: